RETIREMENT TRIP #7

City of Rocks Really Rocks

Although temperatures hovered in the high

30’s this morning in Burley, Idaho, the wind had subsided. It was going to be a lovely day.

We headed for City of Rocks, a place

known for extremes in temperature.

“I read that it can be freezing there on

July or August mornings and reach more than 100 degrees by afternoon,” said

Andy.

In Declo we passed a group of high school

age kids carrying bright orange bags. They were cleaning the highway at 9:00

a.m.

“Community service,” said Andy. “It must

be part of school here.”

“That’s good,” I said.

|

| Old Conestoga wagons remind visitors to City of Rocks that this was one of the original trails West. |

“Hopefully these kids who are cleaning up

will come to understand that and pass it on,” I told him.

We went by Pomerelle Ski Area. It was certainly high enough and mostly

treeless. Huge new homes graced the

slopes on adjoining mountains. They all

had sprawling fields of rich grassland, herds of Black Angus and arching entry

gates to the properties: Mountain Aire,

Grand View, Little Cove, Aria. Even the

cemetery was called Sunny Cedar Rest. We

chuckled.

|

| Rocks in the background typify the scenery ahead. |

Two Conestoga wagons marked the Visitor

Center entrance to City of Rocks National Reserve. They were reproductions, but they looked real

enough. We went in to watch the

nine-minute introductory film. This area

was a key landmark on the California Trail.

|

| Andy checks out Camp Road, now gravel, that served as a byway for early pioneers. |

At the entrance the road turned to

gravel, but it was well packed. We

stopped at the sign and then headed for the first overlook, a mile uphill.

|

| Camp Road winds uphill into the rocky outcroppings. |

“I’d sure hate to meet someone coming the

other way,” said Andy. Luckily, we

didn’t, going up or down.

Two campers were parked at the overlook,

even though a sign at the turnoff suggested, “No trailers.”

A cottonwood tree still thrived in front

of the ruins of a house. “There are

still in-holdings here,” said Andy. “The

equipment is current. That’s why the

gate is pad-locked.”

|

| From the entrance we can see the jumbles of rocks in the distance. |

|

| Early pioneers imagine a city here with granite intrusions from ancient times. |

The granite outcroppings at Camp Rock

were magnificent. In every direction,

there was a picture.

At Camp Rock we met Archeologist Tara,

Chief of Integrated Resources. “If you

look over here,” she pointed to the back side of the granite outcropping,

“you’ll see a profile of a man. Next to

it he carved ‘Wife Wanted.’ He was

advertising!”

“And over there,” Tara continued, “is the

signature of Ida Fullinwider. She was only

16 when her family came through here as pioneers.”

|

| Pioneers leave their mark but not for eternity, as signatures slowly erode from the face of Camp Rock. |

In 1930 there were hundreds of names recorded on Camp Rock by emigrants as thousands of them headed to the West. The historic records are disappearing rapidly--some due to nature and some due to malicious and careless human beings.

Tara and I talked about the ancient graffiti. Some of it was done with axel grease, since the granite is so hard to carve.

Tara and I talked about the ancient graffiti. Some of it was done with axel grease, since the granite is so hard to carve.

“I am concerned about Register Rock,”

said Tara. “There is no fence there, so

people are tempted to touch, and the oil on their fingers can’t be good for the

rock.”

“Maybe they are tempted to touch

history,” I suggested.

|

| From Camp Rock every direction offers a picture of scenic beauty. No wonder the pioneers were fascinated by the Twin Sisters. |

“Could be,” she agreed, “but most

probably don’t even think about that.

Those old ones are starting to fade.”

She pointed to a couple signatures nearby. “The older ones are probably being worn away

by the salt from Great Salt Lake in Utah.

And we have cows roaming here as well.

We do have some thoughtless modern graffiti on the other side. We have tried to wash off the newer ones.”

“So can you sandblast the modern stuff?”

I asked.

“Not really. It’s too close to the old ones.” Tara sighed.

I knew how she must feel to see such

treasures fade away.

|

| Twin Sisters represent granite intrusions from two different but similar geologic intrusions millions of years apart. |

We drove on to Twin Sisters, two gigantic

granite peaks. The movie had explained

the left sister was one hundred times older than the right one, but both were

formed the same way. Molten lava had

intruded other rock layers deep beneath the surface. It hardened, remained under pressure and metamorphosized

into granite. Later, the whole layer

uplifted and the softer surrounding rock eroded away.

|

| Twin Sisters represent different geologic times but the same geologic formation process. |

The younger sister was Almo Pluton

granite. The older one is from the

ancient Green Creek Complex. While only

the tops of the plutons are visible, these ancient granites are like an open

window into the earth’s crust.

Once exposed, granite is subjected to

weathering by wind, freezing and thawing water, salt, and other naturally

corrosive chemicals. These forces work

to create pinnacles, pan holes, honeycombs, windows and arches.

Register Rock was our next stop. I snapped a picture of swallows’ nests

clinging to the rock crevices. The

swallows were long gone.

|

| The imaginations of pioneers created names for the unusual formations as they camped at Register Rock. |

The 14,407-acre City of Rocks Reserve

exhibits what some scientists call a biogeographic crossroads, where many

plants and animals are on the edge of their habitat range. More than 750 species of plants and animals

have been documented within the Reserve.

|

| Names are still visible from the 1800's when pioneers traveled West in search of new opportunity and better lives. |

Pioneers through here on the trail West

left their marks between 1843 and 1882, the year of the first pioneers on the

Oregon Trail and the year of the completion of the Short Line railroad when

Conestoga wagons became obsolete and a thing of the past. Many signed their names on the rocks.

In 1843, those who came sought land, but

once gold was discovered in California in 1849, thousands were enticed to hit

the trail seeking their fortune.

The first emigrants followed the

landmarks described by fur trappers and early explorers. Others soon followed wagon ruts and published

descriptions.

|

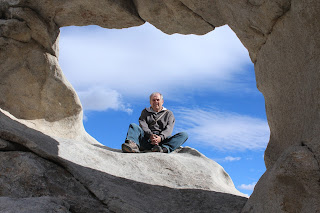

| High above the world but an easy climb, Andy sits in the sky at Window Arch. |

The area served as a stagecoach way

station after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Homesteaders moved in to graze cattle in the

1870’s. Today it is a popular mountain

climbing destination, with more than 700 developed routes, ranging in height

from 30 to 600 feet of textured rock surface.

“There are some climbers,” said

Andy. “This area is said to be as

challenging as Yosemite for rock climbing.”

|

| A climber scales the face of Elephant Rock. |

“Oh, stop,” I said, looking up from my

writing. I hopped out to capture a girl

scaling the lower part of Elephant Rock and a guy just mounting the crest of

the giant formation.

|

| Sue tries her hand...and foot at rock climbing at Window Arch. |

Window Arch was a 300-foot walk from one

of the campgrounds. What a gorgeous

place to camp. We walked out to the

arch. The aspen trees were almost all

bare, and a chilly wind gusted through when the sun slipped behind a cumulus

cloud. Yellow rubber rabbitbrush accented the outcroppings. We peeked through Window Arch. Other monoliths and aspires soared behind us.

Parking Lot Rock had a .6-mile

trailhead. But the four other cars in

the lot were probably climbing.

Immediately, I saw a guy scaling the side. It looked like he was free climbing.

“I can’t watch,” said Andy. “I can’t stand to look at it even if he has a

rope. And I don’t think he does.”

|

| Parking Lot Rock attracts climbers because of its difficult, challenging crevices and smooth top. |

Small patches of prickly pear cactus grew by the trail under junipers and cedars, all dwarfed by the cold.

At the base of Creekside Towers, Andy

grabbed my hand and said, “You can do this.”

Together we climbed about 25 feet.

“And I had to work to get you that high!” he teased.

Clouds had started to move in. In spite of the chilly breeze welling up, we

waited for the sun to clear the clouds for better pictures. The climb back out called for a little

energy. We had driven up to 6,830 feet

so elevation mattered!

|

| In spite of rock outcroppings and rock jumbles, the panorama spreads before us. |

|

| From Creekside Towers, every direction offers spectacular views. |

|

| From our 25-foot high perch, we photograph the granite face of Creekside Towers to the left. |

Back in the Parking Lot Rock parking lot,

we watched the climbers again. She had

reached a precarious ledge, and he waited patiently about ten feet from the

top.

|

| Climbing partners scale the cliff wall at Parking Lot Rock in City of Rocks. |

“It must take nerves of steel to do

that!” I thought out loud. And here I

had made it a whole 25 feet!

The next turnoff took us to Bread Loaves,

two very boxy formations. Now clouds

predominated, and only small patches of blue poked through. We stopped again for pictures. The trails here were all long ones, and the

sign read 6,900 feet. Higher meant

colder.

Our final stop at 7,200 feet was The

Finger. “I don’t know which one though,” said Andy

|

| Jumpers in body suits and with parachutes legally "fly" from Perrine Bridge, the only legal bridge launch site in the U.S. |

Turning into the uphill cutoff, he said,

“I think we could get rain.” Huge grey

clouds had covered the sky overhead and blanketed the formations. “It’s ten miles out, once we leave the

junction, and this road wouldn’t be good once it got wet.”

We met a truck on the way down, but it

wasn’t until the road had widened. “I’m

sure glad I didn’t meet him a while ago,” said Andy.

|

| The Snake River continues to carve the land around Twin Falls. |

The pamphlet said that many pioneers were

forced to lighten their loads at City of Rocks.

They left behind precious items before embarking on the most dangerous

part of their trek ahead—Granite Pass, Forty-Mile Desert and the Sierra Nevada

Mountains.

|

| Water pours from the cliff side in downtown Twin Falls. |

We only had to drive to Twin Falls. And that was far enough!

No comments:

Post a Comment